The Gospel tells us that Herod Antipas, king of Galilee, ar rested John

the Baptist and had him executed. The story is well known in all its gruesome

details: Herodias' grudge against John; Herod's birthday party which was

attended by 'the chief government officials, army officers and leading citizens

of Gali lee'; Salome's dance; the girl's demand for John's head to be brought

on a dish; and John's execution itself. (1) The news shocked Jesus. He withdrew

for some time to a lonely place, probably on the other side of the lake.

(2)

The Gospel tells us that Herod Antipas, king of Galilee, ar rested John

the Baptist and had him executed. The story is well known in all its gruesome

details: Herodias' grudge against John; Herod's birthday party which was

attended by 'the chief government officials, army officers and leading citizens

of Gali lee'; Salome's dance; the girl's demand for John's head to be brought

on a dish; and John's execution itself. (1) The news shocked Jesus. He withdrew

for some time to a lonely place, probably on the other side of the lake.

(2)

Jesus was shocked, but he was not surprised. He knew the political realities of the time. He was aware of the power structures that kept his people in a tight hold. As is always the case, power ultimately rested on economic control. In this chapter we will look at Jesus' world from this perspective. It will help us grasp the distinctively religious vision which Jesus proposed.

At the time of Christ Palestine was part of the Roman Empire. This meant that the Roman Emperor who resided in Rome, was the highest political authority. For all practical purposes Palestine was a colony, a province ruled by Rome through local leaders or through Roman administrators. When Jesus began his ministry the Emperor was Tiberius and the Roman Governor of Judaea was Pontius Pilate. Galilee was not ruled directly by the Governor, but by a local king, Herod Antipas. (3)

Who were these Romans?

They came from Rome, a city in Italy that produced good soldiers and capable organisers. Through centuries of military successes, Rome began to flourish with ever greater wealth and prosperity. To keep up this prosperity required further conquests. In the course of time this led to the establishment of a formidable empire that engulfed all the countries around the Mediterranean Sea, from Spain in the west to Syria in the east, from Britain in the north to Egypt in the south.

The Roman empire maintained its control through military domination, political rule and efficient taxation. The Roman armies excelled in discipline and the imaginative use of the latest technology. In Italy itself Roman citizens were drafted into the legions; in countries outside Italy, foreign mercenaries were enrolled. But these too were drilled in all the skills the Romans mastered so well: hand-to-hand combat, assault and defence in formation, building fortifications and siege works, subduing unruly crowds and marching long distances at short notice.

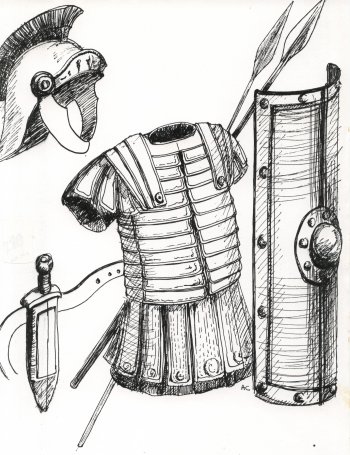

Roman soldiers were well armed for battle . A short tunic covered with brass plates protected the body.

A helmet was worn and a buckler. The lance, the javelin and a stubby, two-edged sword functioned as their main weapons.

To keep the troops mobile and well supplied called for good lines of communication. The Romans developed a network of paved roads that connected all corners of the empire to Rome. Sea routes were supervised. A fleet was maintained, new ports opened.

The Romans were too intelligent to impose one rigorous, uniform rule on all subjected nations. They encouraged local government, as long as the indigenous rulers ensured the steady flow to Rome of taxes and favourable trade. The status of the Roman 'man-on-the-spot' varied from being merely a military observer to being totally in charge. The Roman strong man could be a proconsul, a legate, a procurator or a prefect.(4)

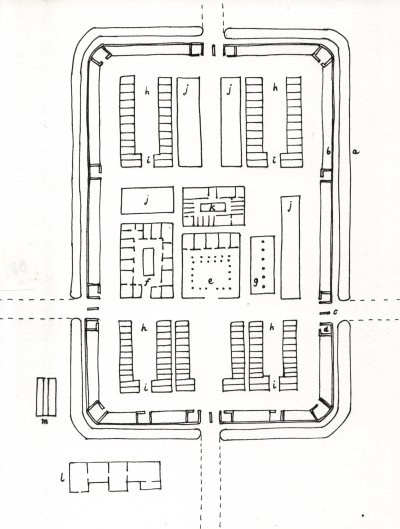

The Romans had a standard arrangement for their army camps (see the illustration below).

A fortified camp (castra) was occupied by a cohort of six hundred men.a. defensive ditch b. rampart wall c. twin gates with d. a guard room e. military headquarters f. house of the tribune in command

g. granary h. barracks for legionaries i. officers' quarters for centurions j. workshops and stores k. hospital and clinic I. baths m. latrines

The Romans recognised Palestine as a particularly difficult country because of the Jews' opposition to foreigners on religious grounds. The Emperors tried to cooperate with a number of competing political factions. Eventually they settled on the Herodian family. Their support of Herod the Great brought a measure of success. He managed the local politics well and remained loyal to Rome. Herod's sons proved more of a problem. Gradually the Romans took more and more direct control over the province. This would provoke the Jewish rebellion of 67 AD and the Roman-Jewish war (68 - 70 AD) that resulted in annexation, destruction and exile.

For the ordinary people in Galilee it mattered little who ruled at the top. They felt the daily pressure of heavy tax burdens and of the trade monopolies the Romans had imposed. The common man and woman saw the world as a pyramid of oppressive powers with themselves at the bottom of the heap. Slaves and servants were subject to their masters. These were responsible to land owners, local governors and petty officials. These in turn were under supervision of Herod's court in Tiberias. Herod Antipas himself was under constant control of Roman colonial power.

If in the land you see the poor oppressed and right and justice trampled under foot, do not be surprised. For every official has another higher than himself on top of him, and above these are others higher still.... 'The produce of the earth is for all', they will tell you. 'Farming supports the king.' (5)

|

GOVERNMENT OF PALESTINE 63 BC Pompey conquers Palestine for Rome.39 BC Herod the Great begins to rule Palestine with the support of Emperor Augustus. 4 AD Jesus is born in Bethlehem. Herod the Great dies. Augustus divides Palestine among Herod's sons.

7 AD Augustus deposes Archelaus. From now on Roman Governors rule Judea and Samaria. 26 AD appointed Governor of Judea and Samaria. 27 AD Jesus begins his public ministry in Galilee. 30 AD Jesus is put to death by Pontius Pilate in Jerusalem. 36 AD Pontius Pilate deposed as Governor. 39 AD Herod Antipas dies. |

It was the Greeks who introduced more efficient ways of farming to Galilee, as they had done in other parts of the Middle East. Under the Ptolemaid kings of Egypt, and later the Seleucid kings of Antioch, these improvements were applied mainly to the 'crown lands', estates which were immediate royal property and over which the king appointed his own managers.

To the traditional crops of wheat, barley, olives and vines, new crops were added of greater economic value like balsam in the plain of Gennesareth, flowers for honey, pomegranates and mushrooms. Varieties of high yield were selected and bred. Wells were dug for systematic watering and canals for irrigation. (6) Farming operations like ploughing, sowing, wee ing, pruning and harvesting were undertaken by seasonal workers under supervision of permanent staff. Researchers tells us that a revolution was taking place, a change over from an economy of 'mutuality' to an economy of 'agro-business'. (7)

The traditional farmer produced a limited range of goods: wool, grapes and wheat, perhaps. These were partly used for the family's own needs, partly exchanged for other goods, like oil and wine, which were also needed by the family. (8) In agro- business goods were turned into money. Traditional farmers might also sell some produce for cash, but only to facilitate the exchange process; they looked on farming as way of living, not as an industry.

Business farms tended to specialise, or, just the opposite diversify, for purely commercial reasons. Vast expanses of land were devoted to one crop. The harvest would be stored in huge barns. Export markets were sought where the produce could be sold for the maximum profit, sometimes overseas so that daughter industries grew up: the fabrication of amphoras ((9) for oil and wine, the construction of ships to transport the merchandise. The ultimate aim was monetary gain, part of which the owner would plough back into his business to improve performance.

The Holy Land, including Galilee, could have benefited a lot from such an agricultural revolution. Unfortunately, the development got side-tracked in a number of ways. First of all, the improvements hardly touched the small landowners. Farmers in the villages who managed to hang on to their own plot of land, continued to farm in the old traditional ways. Secondly, a small group of elite families began to concentrate wealth. They acquired the previous crown lands and any other estate they could lay their hands on. In Galilee, for instance, Herod Antipas possessed such estates, as did a number of his officials. Some rich land owners lived in Sephphoris, Tiberias and Jerusalem.(10)

These landlords were often reluctant to spend capital on agricultural change; they simply wanted to make as much profit as possible. Capital was spent on amassing more land. Small farmers frequently could not meet the debts they had incurred by a combination of drought, high taxes, disease in the crop or other disasters. The rich land owner would step in, buy the farmer out and make him work for himself as a tenant.

The figure of the landlord can be recognised in a number of Gospel passages.

* When Jesus spoke of 'those dressed in fine clothes who live in palaces', (11) people knew he meant their absentee landlords who owned splendid residences in Hellenistic cities.

* A prominent citizen declines the king's invitation to attend the wedding of a prince because 'I've just bought a field'. (12)

* One landlord feels he should build more spacious granaries because of a plentiful harvest. 'I've made it', he says to himself. 'I'm alright for years to come. From now on I can eat and drink and enjoy life.' (13)

Jesus also refers more than once to the post of the manager appointed by the landlord. These managers supervised the tenants, collected their master's share and kept the accounts. Probably they received a percentage of the income as payment.

* A manager of crown lands owes the king 10,000 talents (34

kilograms of gold each), probably in revenue he has failed to collect. The king

cancels this debt - an amount too large for ordinary people even to imagine!

The manager then meets one of his tenants who owes him 100 drachmas

(silver coins of 4 1/2 grams each), but he does not show the poor man the same

generosity the king i had shown him. (14)

* A rich man who goes to a far

country, entrusts ten, five and one talent to three servants. The first two do

good business with their master's capital. They are rewarded by being put in

charge of 'ten villages' and 'five villages'. This undoubtedly means that they

are now made managers of large estates which virtually encompassed whole

villages. (15)

* A crooked manager who is going to be sacked by the land

owner, makes friends of his tenants by reducing their debts on the credit

notes. (16)

Jesus knew, and deplored, the abuses and injustices that accompanied the interaction of landlord, manager and tenants on large estates. But he did not condemn the system as such. In fact, he saw many human angles in it from which we can learn to create a better world. We too are managers - in the Father's kingdom! From secular managers we can learn planning and foresight, creative enterprise and a sense of responsibility.

'The children of this world are more astute in handling their affairs than the children of light'. (17)

'To every one who achieves something, more will be given. (18)

The parables teach us to keep our priorities right, to remember God's values and to treat others as God would treat us.

Did Jesus address these parables to landlords and managers?

Yes and no.

Among his audience there were some who belonged to this class. One of the women who followed Jesus was 'Joanna, whose husband Chuza held a post at Herod's court'. Then there was the rich young man who wanted to be Jesus' disciple and for whom the family estate proved an insurmountable obstacle. (19)

But the majority of his audience were ordinary people. They knew landlords by repute and estate managers from day-to-day contact.

We have already met the common folk of Galilee, when we discussed Capernaum and Nazareth. Now we must assess them from an economic point of view.

In the countryside there were still quite a number of farmers who owned their own plot of land. (21) The father Jesus speaks of in his parable of the prodigal son, was going to leave the family property to his two sons. (22) Another man owned a small vineyard and depended on his sons to work in it. (23) Though independent, these subsistence farmers were not likely to become millionaires.

Taxes weighed heavily on profits. The Romans levied a poll tax for each member of the family and took a quarter of the produce as land tax, to be delivered every second year. The religious authorities in Jerusalem exacted a tithe and Temple tax. Enterprising farmers who wanted to sell their produce outside their region, faced crippling custom duties at each border. A sales tax on market goods was operated in cities and towns. What remained was scanty indeed. (24)

Farmers had no insurance against drought, mildew, locusts or other natural disasters. Their stores were often plundered by gangs of rebels or highway robbers. Passing soldiers were billeted in the villages. None of these misfortunes excused farmers from paying their taxes. Loans might tide them over for a while; often they ended in total ruin as interest could be as high as 25 per cent. Jesus refers to the hard reality of a householder being forced to sell himself, his family and his property to settle a debt. (25) At other times he mentions debtors being thrown into prison and subjected to torture until the last penny had been paid up. (26)

Many small farmers escaped such a drastic fate bv agreeing to sell their freehold and become tenants instead. (27) It hardly improved their condition. Now they had to hand over even more of their crop as the owner's share, while having lost ownership of the land. (28)

Against this background we can understand the parable of the tenants of the vineyard. They were hostile to the owner and to the various middlemen the owner sent to collect his share. The vineyard in this parable is Israel, and God the owner.(29)

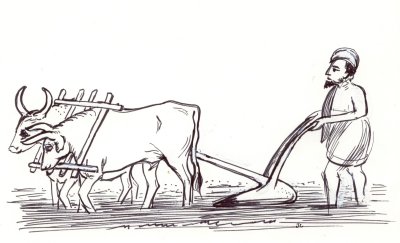

'No one who puts his hand on the plough and looks back is fit for the kingdom of God' (Luke 9,62).

Farmers used rather primitive ploughs. They were not so much preoccupied with keeping the furrow straight as with keeping the plough down.

Since the soil was bumpy and dry, a farmer needed to press the plough down all the time to ensure that the blade would cut the soil deeply enough.

It is this single-minded commitment a disciple should have.

'Put on my yoke and learn from me .... For my yoke is easy, my burden light' (Matthew 11,29-30)

Jesus uses two parallel images here: the yoke put on an ox who pulls the plough and a burden put on a donkey for transportation.

The images of the Gospel speak with more force the more we can vividly picture daily life in the Holy Land.

A book I can recommend is:

R.GOWER, Manners and Customs of Bible Times. Amersham-on-the-Hill 1987.

Jesus compares the leaders of Israel to hostile tenants who oppose God's prophets and, when they meet Jesus, say: 'He is the heir. Let us kill him!' (30)

The small craftsmen in the towns and villages were so closely associated to the farmers that they did not really constitute a separate class. Here we may reckon carpenters(=builders), potters, the village scribes, fishermen, local merchants and shopkeepers. (31)

Lowest on the scale of social prosperity lived the rural proletariat, the people who neither owned nor leased land and exercised no skilled profession. These were casual workers taken on for the day, (32) shepherds, (33) hired servants (34) and slaves (35).

These then were the ordinary people of Galilee, a motley crowd of mixed origin, varied status and divergent occupation, yet roughly sharing the same conditions of life. For all ultimately lived off the land. (36)

The problem was: did they really share what they had in common? Or did they fight each other in heartless competition?? The rule of mammon Jesus, we can be sure, was appalled by the way the powerful exploited the poor. But we misunderstand him if we think that his main concern was the overthrow of Galilee's rulers. He upheld the authority of the Roman emperor saying: 'Give to the emperor what belongs to the emperor'. (37) He did not condemn the system of agro-business as such. He did not preach the kind of social revolution advocated by political reformers.

As usual, Jesus' vision of reform was far more fundamental, and therefore ultimately far more subversive to systems of exploitation. Jesus saw that one root cause of the social disorder lay in allowing money to dominate relationships. Land, capital and profit dictated what people said and did to each other.

And this basic submission to greed and self-interest affected the ordinary people as much as the very rich. The poor might have an initial advantage: 'Happy are you who are poor, the kingdom of God belongs to you! (38), but only if their true treasure is with God. (39) For among the ordinary people too there were those who were better off but did not help their neighbours; or those who tried to climb the economic ladder over the backs of others.

* Zaccheus was not a wealthy landlord. He was probably a farmer's son who wanted to advance in life and who chose to become a custom official because of its lucrative prospects. He made profits on duties squeezed out of other people like himself. (40)

* Stealing was only too common. People kept their best clothes and jewellery in a locked chest, but even then they were not safe. (41)

* A woman has saved ten drachmas (= ten days' wages) for some special purpose. When she finds one is missing, the suspicion of a theft may have entered her mind. Was it her husband? One of her children? Or, perhaps, she has dropped the coin. Being silvery in appearance it is not easily spotted on the clay floor. Imagine her relief when she does find it! (42)

* Anxious farmers stayed awake at night fearing thieves might plunder their granary.(43)

* Those appointed to oversee a large household often treated their fellow servants badly. They beat them up, withheld their wages or failed to give them proper food and drink. (44)

* A spiteful villager might sow weeds among the wheat crop of a neighbouring farm. (45)

* Travellers might find a robbed and wounded fellow traveller on a lonely desert road and leave him to die. (46)

People's hearts had grown hard. They thought no longer as God does - who prizes and loves each human person. They had begun to worship money rather than God.

'No one can serve two masters at once.

He will either hate the first and love the second,

or treat the first with respect and the second with contempt.

You cannot serve both God and money.' (47)

What the world needed was a new scale of values.

1. What are your comments on this incident:

A man in the crowd said to Jesus, 'Master, tell my brother to give me my share of our inheritance'.

'My friend', Jesus replied. 'Who appointed me judge or arbitrator in your case?'

Then he stated: 'Be on your guard against every kind of greed . . . Luke 12,13-15

Had you expected Jesus' warning?

2. After recounting the parable of the crooked manager Jesus makes this remark:

'Whoever is faithful in small matters will be faithful in large ones.

Whoever is dishonest in small matters will be dishonest in large ones.' Luke 16,10

What does Jesus mean?

3. Vatican II enunciates this basic economic principle:

In the sphere of economics and social life, the dignity and total vocation of the human person must be respected and promoted, along with the welfare of society as a whole. For human beings are the source, the centre and the purpose of all socio-economic life. The Church in the Modern World, no 63

Can you see some implications of this principle for our present-day world?

| 1. Mark 6,17-29; Matthew 14,3-12. | 2. Matthew 14,13. | 3. Luke 3,1. |

4. It was thought for a long time that Pontius Pilate was 'procurator'. In a recently found inscription he is given the title of 'praefectus', one notch lower on the hierarchical scale.

5. Kohelet 5,7-8; freely translated.

6. One example is the royal estate of Beth Anath. A certain Glaukias reports (in a letter dated 257 BC) that new strains of vine have been introduced to the estate and that another well has been dug. The estate, we are told, has 80,000 vines in culture. M.HENGEL, 'Das Gleichnis von den Weingartner im Lichte der Zenonpapyri', Zeitschrift der neutestamentlichen Wissenschaft 59 (1968) pp. 1 - 39.

7. S.FREYNE, Galilee from Alexander the Great to Hadrian, Wilmington 1980, pp. 170 -176; see also Galilee, Jesus and the Gospels, Dublin 1988, pp. 155 - 175.

8. Jesus lifts the old principle of mutuality to a higher level when he says: 'Do to others as you would like them to do to you; that is the meaning of the Law and the Prophets.' Matthew 7,12.

9. These were earthenware vats that could hold about twenty litres. Two handles for lifting were fixed on the side. The top could be sealed with a tight-fitting cap. The bottom was pointed for easy storage on top of (and between) other amphoras.

10. D.J.HERZ, 'Grossgrundbesitz in Paliistina im Zeitalter Jesu', Palästinajahrbuch 24 (1928) pp 98 -113.

| 11. Matthew 11,8. | 12. Luke 14,18. | 13. Luke 12,16-21. | 14. Matthew 18,23-34. | 15. Luke 19,11-27. |

| 16. Luke 16,1-9. | 17. Luke 16,8. | 18. Luke 19,26. | 19. Luke 8,1. | 20. Matthew 19,16-24. |

21. M.GIL, 'Land Ownership in Palestine under Roman Rule', Revue Internationale des Droits de I'Antiquité 17 (1970) pp. 11 - 53.

| 22. Luke 15,11-31. | 23. Matthew 21,28-32. |

24. F.C.GRANT, The Economic Background of the Gospels, Oxford 1923; E.SCHUERER, A History of the Jewish People in the time of Jesus, New York 1961, pp 189 - 192.

25. Matthew 18,25. Some records seem to indicate that there was a thriving slave trade from Palestine to Egypt.

26. Matthew 5,25-26; see also 18,30 and 18,34.

27. It has been claimed that the tenants were actually slaves or bondsmen, but that was apparently not the case. Agricultural slavery, as practised in Italy, was not common in the Middle East. P.BRIANT, 'Laoi et Esclaves Ruraux', in Actes du Colloque 1972 sur I'esclavage, Paris 1974, pp 93 - 133; esp. pp 96 - 106.

28. Some tenants paid a share of the crop, others had to pay a fixed amount irrespective of the prevailing conditions. APPLEBAUM, 'Economic life in Palestine', Compendium Rerum Judaicarum ad Novum Testamentum, ed.M.STERN and S.SAFRAI, vol.2, pp. 631 - 700.

| 29. Isaiah 5,1-7. | 30. Matthew 21,33-46. |

31. The Hellenistic world had a middle class with a more distinct social niche. A.N.SHERWIN-WHITE, Roman Society and Roman Law in the New Testament, Oxford 1963, pp. 139 - 140. See also W.MEEKS, The First Urban Christians, London 1984.

| 32. Matthew 20,1-16. | 33. John 10,12-13. | 34. Mark 1,20. | 35. Luke 17,7-10. |

36. A.OPPENHEIMER, The Am Ha-Aretz. A Study in the Social History of the Jewish People in the Hellenistic-Roman Period, Leiden 1977.

| 37. Matthew 22,21. | 38. Luke 6,20. | 39. Matthew 6,19-21. |

40. J.R.DONAHUE, 'Tax Collectors and Sinners. An Attempt at Identification', Catholic Biblical Quarterly 33 (1971) pp 39 - 61.

| 41. Matthew 6,20; Luke 12,33. | 42. Luke 15,8 -10. | 43. Matthew 24,43. |

| 44. Luke 16,1-6. | 45. Matthew 13,24-30. | 46. Luke 10,30-37. | 47. Matthew 6.24. |