In this last chapter of the book we shall pay special attention to

Jesus Christ. His vision has been crucial in shaping the religious convictions

of what is now one fourth of humankind. What he did as the Incarnate Son of God

has had lasting consequences for all human beings.

In this last chapter of the book we shall pay special attention to

Jesus Christ. His vision has been crucial in shaping the religious convictions

of what is now one fourth of humankind. What he did as the Incarnate Son of God

has had lasting consequences for all human beings.

I must start by pointing out a frequent misconception. Some people have a very naive idea of the mystery of the Incarnation. If Jesus was God's Son, they think, he knew from the start everything there was to know. Therefore, he must have expressed in the Gospel a detailed master plan for all time to come. All we need to do is to read the Gospels attentively and execute what Jesus tells us to do.

This is not the way the Incarnation happened. When 'the Word was made flesh', (John 1,14) we received a high priest who was like us in every respect, except sin. (Hebrews 4,15.) Note: in every respect. That means: he thought and spoke in a human language. He had to learn and discover new things as we have to do. He shared the knowledge and the ignorance of his contemporaries. Only in that way did he become truly like us.

The Gospels confirm this. Jesus was no walking divine encyclopedia. As a child he grew in wisdom and charm. (Luke 2,52) Jesus could be amazed when something happened which he had not expected. (Matthew 8,10; Mark 6,6) The Gospel episodes show that he responded to events and to people as he encountered them. Jesus was terribly upset when he realised that his opponents were planning to kill him. (1)

Jesus' vision of the world as 'the kingdom of his Father', contained the seeds of dramatic revolutionary change. But it is not correct to say that he foresaw all its implications or future developments. Jesus' human limitations did not permit him to.

Neither was it necessary for him to know or spell out in detail what needed to come. As a good, enabling teacher, he left the application and working out to future generations. (2)

This means that we should not expect to find in the Gospels a clear expression of those social principles that are now part of our Christian heritage. Among them: democracy, the abolition of slavery, the freedom of speech, racial equality, a nation's right to self determination, the emancipation of women, and a just division of the world's resources.

Jesus' role in history was far more radical than spelling out the details of a future society. By being 'God among us (Matthew 1,23) he brought about in his very person the start of a new reality. For the presence of God was not presented in the image of a powerful, rich, political leader. It was seen in the face of Jesus, a peasant with a Galilean accent. 'Who sees me, sees the Father', Jesus said. (John 14,9)

The Gospels stress that, from the first moment of his life, Jesus identified fully with those considered the least and the lowest. Luke narrates on purpose how the infant Jesus was born in a stable built for animals and how he was laid in a manger, the way poor people take care of babies. To welcome him, God did not choose a delegation of the political or religious elite, but a group of shepherds - a despised and impoverished social class of people. (3)

Jesus lived most of his life in Nazareth, an incredibly small hamlet. He was 'the builder', that is: the local handyman who took on all jobs that were going: sharpening a tool, repairing a tottering wall, fixing a leaky roof or replacing a wooden door. (4) As a travelling preacher, he walked barefoot, with no clothes except for what he was wearing, with no purse for money nor a bag for provisions. (5)

Jesus died the death which the Romans had reserved for rebellious slaves. That is why Paul says:

He emptied himself

to assume the condition of a slave

and became like (other) human beings.

And as a human being, he humbled himself

and became obedient unto death,

yes, death on a cross. (Philippians 2,7-8.)

The moment of Jesus' final surrender to the love of his Father was also the moment of his fullest identification with human beings in their rejection and suffering. For God loves human beings and has empathy with their suffering. That is, no doubt, the meaning of his exclamation:

'When I am lifted from the earth,

I will draw all human beings to myself.' (John 12,32.)

Jesus, the peasant from Galilee, the handyman, the barefoot preacher, died on a cross as the scum of the earth. In his hours of agony he descended into the depths of human loneliness and rejection, and became one with slaves, losers and underdogs. But he rose again to life and glory, and rising he took all human beings with him.

When we were baptised in Christ Jesus, we entered the tomb and joined him in death.

This happened in order that, as Christ was raised from the dead by the Father's glory, we too in like manner might walk in the newness of life. (Romans 6,4)

Notice that no one is excluded, whatever their race, class, sex or social status.

If we want to read the Gospel more sensitively, we have to distinguish three levels:

the prophetic actions of Jesus;

the liberating effects of redemption;

the presence of the Risen Christ.

Let us work out this approach with regard to women. We ask ourselves: does Jesus make women free?

When we try to reconstruct Jesus' attitude to women, we detect an awareness of their presence among his audience. Jesus draws his examples from the life of women, no less than from the life of men. He knows that women keep their treasures in boxes, and that they light a lamp at dusk. (Matthew 6,19-21 and 5,15-16.) He speaks of children playing in the market place and of girls waiting for the bridegroom at a wedding. (Matthew 11,16-19 and 25,1-13) He often tells his parables in pairs, with a story about a woman running parallel to a story about a man:

the housewife who mixes leaven in the dough/ the farmer who plants a mustard seed;

the woman who lost a coin/ the shepherd who lost a sheep;

the widow pestering the judge/ the friend waking up his neighbour at night. (6)

We can be sure that Mary, Jesus' mother, had a great influence on him. Jesus learned many of his ideals from her. She must have encouraged him when he began his public ministry. A trace of this has been recorded in the Gospel of John. During the wedding at Cana it was Mary who urged him to perform his first miracle. 'My hour has not yet come', Jesus protested. But when she quietly insisted, he changed his mind and ushered in the messianic era by turning water into wine. (John 2,1-12)

|

The symbolism of wine was well understood by Hellenists. Wines of differemt brands were traded all over the Middle East in simple earthenware amphorae (tall, two-handled jugs; see an earlier illustration ). Before being served, however, wine was poured into a large, decorative vessel as shown here. This was known as a mixing vat since flavours were blended.

At various crucial stages in his own development Jesus gained insight and was prompted to action through encounters with women.

* When the woman who suffered of a flow of blood touched Jesus from

behind, 'he perceived in himself that power had gone forth from him'. Perhaps,

Jesus' healing ministry took its beginning from such encounters. (Mark

5,21-43)

* The Syro-Phoenician woman pleaded with Jesus to drive the

demon from her daughter. Jesus refused because he felt his mission was

restricted to his own people. However, the woman argues with him; and Jesus

gives in, thus making a first step on the way to his universal mission.

(Mark 7,24-30)

* In the house of Mary and Martha Jesus meets, perhaps

for the first time, a woman who, like the men who sit at his feet, wants to be

a disciple. Jesus is impressed by this and encourages her 'discipleship' even

if it runs counter to conventional expectations of a woman's role. (Luke

10,38-50 see also 8,1-3)

Jesus also responded to the silent gestures of women: the repentant prostitute who poured ointment on his feet, the widow of Nain who walked behind the bier of her dead son, the woman who was bent double with arthritis, the widow in the Temple who put two small coins in the offering box, and the women of Jerusalem who wept as they saw Jesus carrying his cross.' (7)

From all these and other texts we can be sure that the historical Jesus was very much aware of the concerns of women. He cared about them. He learned from them. He recognised in their needs, and their suggestions, promptings by the Spirit. The forgiveness and reconciliation he brought from his Father, were as much for women as for men. (8)

|

We could now proceed to a deeper level and ask: What use has Jesus' concern been to women? Has it actually resulted in facts of liberation? Has the Risen Christ proved as effective for women as the promise held out by Jesus of Nazareth?

The answer is: yes! The position of women in religion changed dramatically with the coming of Christ. Whereas she had only belonged indirectly to the covenant of Moses, woman was now made a child of God on an equal footing with man.

In the Old Testament, it was only the men who were the immediate bearers of the covenant. It was the male children who were circumcised when they were eight days old. (Genesis 17,9-14) The covenant, therefore, was concluded directly with the men. Women belonged to it only through men - first as daughters through their fathers, and later as wives through their husbands.

It was the men who were expected to offer sacrifices in the Temple. Three times a year, at the three major feasts, all the menfolk were to appear before Yahweh's face. (Exodus 23,17; Deuteronomy 16,16-17.) The women could come along and take part in the sacrificial meal, as did children, slaves and guests. But it was not really their own sacrifice. (9)

In the Temple at Jerusalem, Jewish women could enter inside the wall of separation into the court of women. They were not allowed to proceed further.

The men, on the other hand, could enter the court of Israel. It was this court that faced the altar of holocausts and it was there that the priests accepted the gifts for the sacrifice. When Mary and Joseph presented Jesus in the Temple, Mary had to stay back in the court of women, while Joseph carried the child Jesus and the turtle doves into the court of Israel. It was there, in the women's enclosure, that they met Simeon and Anna. (Luke 2,22-38)

Also in traditional Judaism the same distinction persisted. It was the men who were required to recite the regular prayers. Men had the principal seats in the synagogues. Men could read from the Torah. Only ten males could form the quorum, minyan, required for public prayers. At the age of 13, boys were initiated into their adult religious duties by the Bar Mitzvah ceremony. No such thing existed for girls. (10)

It is with this background in mind that we can appreciate the revolutionary change brought by Christ. For both men and women are initiated into the new covenant by one and the same rite, namely baptism. We have already seen above that in baptism we die with Jesus and rise with Jesus. Both men and women undergo this transformation and come out as 'a new creation'.

On account of this, both men and women share equally in the eucharistic meal and have equal religious duties. These are factual changes with enormous consequences.

Again, let us listen to Paul:

All of you are children of God

through faith in Christ Jesus.

All of you who have been baptized in Christ,

have clothed yourselves in Christ.

Thus there is no longer Jew nor Greek,

free nor slave,

male nor female.

For you are all one in Christ Jesus. (Galatians 3,27-28)

Notice, once more, the revolutionary changes Christ has brought about in the factuality of human relationships to God. But this religious factuality still needs translation into social and ecclesial factuality.

The Churches are still discussing all the consequences. A burning issue is the admission of women to the sacramental priesthood. I trust that ultimately this question will be resolved on the basis of the fundamental equality established by Christ. (11)

This brings me to the third level of approaching the Gospel. How does Christ relate to women today? Can he be a model that inspires them?

Can he, who is 'the radiant light of God's glory and the perfect copy of God's nature', mediate a relationship of modern women to God? (12)

I believe he can and he does; but it may require a new focus in our approach to Christ. And the Gospels already show the way to such a dynamic interpretation. To understand this, we have to return briefly to the situation of the early Christian community. I have already pointed to the fact that, while women in general lived as secondary citizens, some Hellenistic women of the upperclasses had begun to claim a more independent status for themselves, as we can see from the historical records.

They fought for greater equality in matrimonial rights. Marriage contracts that have been found, demonstrate a grow- ing emphasis on securing a wife freedom to divorce, on equal terms with her husband. Her property too was protected. The husband was made responsible for maintaining children from the marriage.

Daughters in such families began to receive an education on a par to that received by sons. They learned to read and write. Some achieved fame in literature, like the Cynic philosopher Hipparchia and the poetess Erinna of Telos. As was the case for boys, education for girls included athletics. It led to women competing in the Greek games in special events organised for them. A talented woman called Herea won prizes for singing and playing the zither at Athens, for a long-distance run at Nemea and for winning a chariot race at Isthmia near Corinth.

|

Wealthy upperclass women began to take more direct control of their own properties. The old rule that required a guardian to vet a woman's transactions, were gradually ignored. Documents have been found that show women as purchasers, sellers, lessors, lessees, borrowers and lenders. Contracts are signed by women themselves. Women are recorded as buying, selling or manumitting slaves.

A number of women are mentioned in inscriptions that list public honours. There were benefactresses who had sponsored some public project. Others held office. Some women had a seat on the city council. Others were magistrates or judges. The percentage of women with such civic responsibilities was admittedly very low, but the very fact that there were some shows that a new class of independent and influential women was taking its place in society. (13)

These developments are also reflected in the New Testament. Among the early Christians we find a number of women of high status and independent means.

Chloë of Corinth was one of them. She sent members of her oikos (house) to meet Paul in Ephesus. (1 Corinthians 1,11) Phoebe was a deacon of the Christian community at Cenchreae, one of the two harbours of Corinth. She also functioned as 'patron' to Paul 'and many others'; which probably implied providing support in cash or goods. She disposed of enough financial means to travel to Rome, presumably on business. (Romans 16,1-2) Such women could obviously hold their own in society.

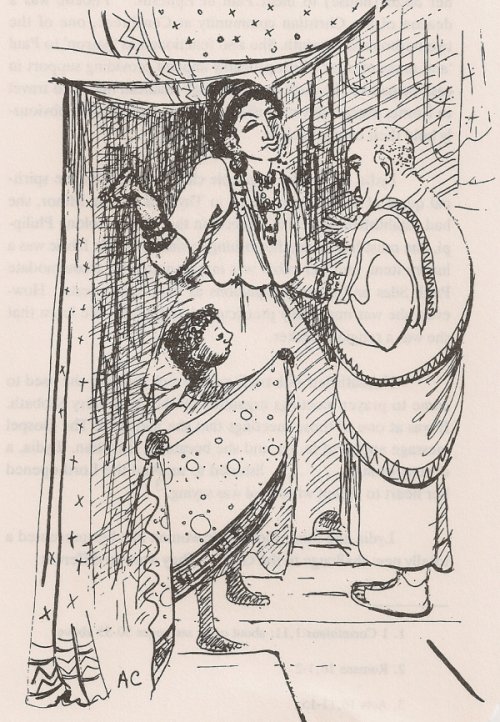

Lydia, the dealer in purple cloth, exemplifies the spiritual quest of such women. Born in Thyatira in Asia Minor, she had established herself in Greece, in the Roman colony Philippi. She must have run a flourishing business. Purple fabric was a luxury item, and her oikos was large enough to accommodate Paul, Silas and other companions as long-term guests. However, she was not totally preoccupied with trade. We learn that she was a religious seeker.

Not satisfied with traditional Greek religion, she used to come to prayer meetings organised by the Jews every Sabbath. It was at one of those meetings that she met Paul. The Gospel message appealed to her and she became a Christian. 'Lydia, a devout woman, .... listened to us. And the Lord opened her heart to accept what Paul was saying. (Acts 16,11-15)

Lydia and other Hellenistic women like her presented a totally new challenge to the Gospel. They were so different from the run-of-the-mill, orthodox women Jesus had met in Palestine.

These Hellenistic 'feminists', in a way, anticipated the generations of independent, tough-minded, emancipated seekers in future generations. The obvious question was, and is, what has Jesus to offer to such women? Can they relate to him in a meaningful manner?

I believe that the Gospels, which were written for Hellenists, both women and men, attempted to address that question. Luke exhibits a great sensitivity to women, not only in the words and deeds of Jesus which he reports, but also in his own theological elaborations. (14) And John has done the same in his presentation of the Samaritan woman. (John 4,5-42)

|

Jesus' encounter with the woman from Sychar undoubtedly reflects a historical incident. John, however, has purposely built this out into a profound discussion. The Samaritan woman should not be taken to be a harlot with no moral standing, as popular preachers sometimes do. For John and his readers she represents the new class of nonconformist Hellenists. True, she may be in need of conversion; but having been able to divorce or dismiss four husbands, marks her as an autonomous and strong-willed person. (15) Moreover, she commanded so much respect in her town that on her testimony many came to believe in Jesus. (16)

In Hellenistic terms, a woman approaching a well to draw water immediately evoked images of a spiritual quest. Religious seekers are often characterised as 'those who are thirsty upon earth'. The dialogue that takes place underscores this meaning. The woman, like spiritual explorers of all times, longs for water that will turn into a spring of life giving water inside her. (John 4,7-14)

Jesus rewards her persistent questioning by announcing an astounding overthrow of established religion. In the future, which was already beginning with him now, external realities such as holy places and temples would disappear as the pillars of religion. The kind of worship God wants is essentially internal. It is 'worship in truth and in Spirit'. It can be offered anywhere. By putting such ideas to the Samaritan woman Jesus singled her out as a person worthy of sharing his insights and hopes.

We should remember that it is the Risen Christ which John presents throughout his Gospel. In this passage it is as if John is saying to the educated women of the Hellenist world: 'Come, meet Christ. Express your longing to him. He understands you. He appreciates you as a person, however much others may ignore you because you are a Samaritan or a woman. He knows you need to be liberated from external structures. He wants to affirm those precious gifts in your heart: the Spirit and the truth. Talk to him about it. He is listening to you.'

Passages like the one in John's Gospel give us the courage to go further and to dissociate the image of the Risen Christ from unessentials that may obscure it. The maleness of the Father-God image and the maleness of the historical Jesus can pose real identification problems to women. These problems can be overcome if we put the gender in its right perspective. The 'fatherhood' of God is no more than a metaphor. God is as much a mother as a father. And the Risen Christ is not a male figure hovering about, but the Spirit in us, the giver of life, who has both feminine and masculine traits. (17)

Juliana of Norwich (1342 - 1416 AD) spoke of Christ as 'Mother'. 'Christ, our saviour, is our true Mother, in whom we are endlessly born and out of whom we shall never come'. (18) Other women relate to the Risen Christ as a close woman friend, or a dear sister. These are not distortions; just as little as representations of Christ in local art who depict him with Chinese or African features. The living Christ transcends the limitations of sex, colour and country of origin. (19)

Since we are all one in Christ, every single person can rightly see himself/herself reflected in Christ. Whatever our social status or colour of skin, Christ has become a new creation in us. Everything that is part of us belongs to him. Nothing human in us is rejected by him. In Christ we transcend all the limitations put on us by others.

As Christians we also believe that Christ has united humankind in a radical way as a 'new creation'.

God has no favourites. Can we afford to cling to our prejudices? Will we be forgiven if we continue to discriminate against any person on whatever ground? Should each one of us not implore Christ to fill us with his Spirit, so that we too can honestly say: 'I have no favourites'?

1. On the 10th of December 1948 the nations of the world issued a 'Universal Declaration of Human Rights'. Its chief tenets are:

Art.l. All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights ....

Art.2. Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status ....

Art.3. Everyone has the right to life, liberty and the security of person.

Art.4. No one shall be held in slavery or servitude. The United Nations and Human Rights, New York 1984.

2. On the 7th of December 1965 the RC Bishops from the whole world, gathered in the Second Vatican Council, endorsed these principles: (The Church in the Modern World, no 29)

'All human beings are endowed with a rational soul and are created in God's image.

All have the same nature and origin. And having been redeemed by Christ, all enjoy the same divine destiny and calling. There is a basic equality between all human beings and it must be given ever greater recognition.

Forms of social or cultural discrimination in basic personal rights on the grounds of sex, race, colour, social conditions, language or religion, must be curbed and eradicated as incompatible with God's design.'

Compare the above two texts. Why does Vatican II put so much stress on God's design in matters of human equality?

1. Matthew 16,21 - 17,8; see J.WIJGAARDS, Inheriting the Master's Cloak, Notre Dame 1985, pp. 83-88.

2. This process is discussed more fully in the WALKING ON WATER course My Galilee My People; see Course Book, London 1990, pp. 95-137.

3. Luke 2,1-20. The scribes looked down on shepherds. Rabbi Joseph, son of Cheninah, is quoted as saying: 'In the whole world there is no more contemptible occupation than that of a shepherd.' With robbers and murderers, shepherds could not be witnesses in court.

4. Mark 6,3; Matthew 13,55.

5. We can deduce this from Matthew 10,9-10; Luke 10,4.

6. Luke 13,18-21; 15,3-10; 11,5-13 and 18,1-8.

7. Luke 7,36-50; 7,11-17; 13,10-17; 21,1-4 and 23,27-31.

8. For a similar analysis of Gospel passages, see Elisabeth MOLTMANN-WENDEL, The Women around Jesus, London 1982; A Land Flowing with Milk and Honey, London 1986, pp. 137-148; Mary GREY, Redeeeming the Dream: feminism, redemption and Christian tradition, London 1989, esp. pp. 95- 103.

9. The principal reason (rationalisation.) was that the wife, like children, slaves and cattle were, in fact, owned by the husband; see Exodus 20,17. 'A good wife is the best of possessions' (Sirach 26,3; see also Proverbs 31,10). The husband could practically divorce his wife at will, she could not divorce him; Deuteronomy 24,1-4). A religious vow by a woman was only valid if it was ratified by her father or husband; Numbers 40,2-17).

10. Only since 1810 AD, in socalled Reform Judaism, has more attention been given to women. A Bar Mitzvah ceremony for women is now common. For an orthodox explanation of women's duties in Judaism, read D.EISENBERG, A Guide for the Jewish Woman and Girl, Brooklyn 1986. A feminist approach to modern questions is presented by the liberal rabbi Julia NEUBERGER in Whatever's happening to Women?, London 1991.

11. See Women Priests, ed. L and A.SWIDLER, New York 1977. For my own view, see J.WIJNGAARDS, Did Christ Rule out Women Priests?, Great Wakering 1986.

12. See Hebrews 1,3. It is impossible to refer here to all the many excellent publications on Christian feminism and spirituality. See the annotated booklists Women, Church and Society published by Lumen (36 Court Lane, London SE 21).

13. Ch.SELTMAN, Women in Antiquity, London 1959, esp. pp. 120-146; S.POMEROY, Goddesses, Whores, Wives and Slaves. Women in Classical Antiquity, New York 1975, esp. pp. 120-148; R.MACMULLEN, 'Women in Public in the Roman Empire', Historia 29 (1980) pp. 208-218.

14. 1. See Luke 1,46-56; 2,36-38; 7,36-50; 8,1-3. B.WITHERINGTON, 'On the Road with Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Susanna and Other Disciples - Luke 8,1-3', Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft 70 (1979) pp. 243-248; R.RYAN, 'The Women from Galilee and Discipleship in Luke', Biblical Theology Bulletin 15 (1985) pp. 56-59; J.BRUTSCHECK, Die Maria-Martha Erzählung, Frankfurt 1986; J.KOPAS, 'Jesus and Women: Luke's Gospel', Theology Today 42 (1986) pp. 192- 202.

15. John 4,18. First-century writers confirm the frequent divorces by some Hellenist women. 'They divorce to marry again; they marry with a view to future divorce'; SENECA, De Beneficiis, III, 16,2. JUVENAL ridicules a woman he knows who disposed of eight husbands in five years; Satires 6, 225-226. MARTIAL mentions the wedding of a certain Telesilla with her tenth husband; On the Spectacles, 6, 7.

16. John 4,39-42. See my commentary on John 4 in J.WIJNGAARDS, The Gospel of John and his Letters, Wilmington 1986, pp. 115-130 and 229.

17. 'Now the Lord is the Spirit, and where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom'; 2 Corinthians 3,17.

18. Juliana of NORWICH, Revelations of Divine Love, transl. J.WALSH, New York 1978, p. 292.

19. I found this dimension of Christ sensitively treated in Kathleen FISCHER, Women at the Well. Feminist Perspectives on Spiritual Direction, London 1989, esp. pp. 75-92.