Hellenism was mainly found in towns and cities. Here Greek

culture and Greek life-style dominated most aspects of society. All the major

cities in the Roman Empire had undergone this influence, and in Palestine too,

many hellenistic cities had been built. Hellenism was a city culture. All

cities tried to imitate, to some extent, the ideal of the Greek city, the

polis. It was the Greeks, with their concern for the rights of citizens,

social functions and power structures, who gave rise to a unique cultural

network that lay across all Mediterranean lands.

Hellenism was mainly found in towns and cities. Here Greek

culture and Greek life-style dominated most aspects of society. All the major

cities in the Roman Empire had undergone this influence, and in Palestine too,

many hellenistic cities had been built. Hellenism was a city culture. All

cities tried to imitate, to some extent, the ideal of the Greek city, the

polis. It was the Greeks, with their concern for the rights of citizens,

social functions and power structures, who gave rise to a unique cultural

network that lay across all Mediterranean lands.

To understand this urban culture, we have to begin by having a good look at the ideal of the Greek ‘city-state’, the polis. For geographical and economic reasons, the ancient Greeks (700 - 400 BC) were divided in small territories about the size of ‘counties’ in England. These territories consisted of cultivated land dotted with small farm houses and little hamlets and one central town.

The total population of such an area was not more than one hundred thousand people, often much less. There were hundreds of small poleis (1) on the Greek mainland and the ad- joining islands.

The free men of the ‘polis’ were called citizens. They could vote in the general assembly of the people which was known as the ekklêsia (2) Since the citizens elected their leaders, city-states were governed by what the Greeks called democracy (literally: ‘people’s rule’). All the official affairs of the state, politics, (3) brought people together to the central town: feasts and occasions of worship in the state temple, assemblies to decide on war or peace, court cases, markets, stage plays and public debates. Since all the important public business was conducted in the town, the town itself (and not just the whole area) became known as the polis.

It is difficult to capture the feeling of a polis in just a few words. Its original ideal can best be described as a self-sufficient, mutually responsible community. A person ‘who avoids the polis’, was someone who hid from the community. ‘I have proclaimed it to the polis’, meant: I have announced it publicly.

Greeks could say: ‘It’s everyone’s duty to help the polis’. A democratic leader was ‘a man chosen by the polis’. In court the accused could appeal to a generally known truth by saying: ‘It’s something the whole polis has heard!’

And it is in this sense that Aristotle made his, so often misquoted, statement: ‘A human being is a political animal’. He meant: ‘A human being should by nature be a responsible member of his community, his polis’. (4)

In later centuries, however, when cities grew larger and when real power came to lie in the hands of local kings and central emperors, the idea of polis shifted from its sense of ‘community’ to its being a ‘city’ with buildings and institutions. The Hellenistic cities of the Graeco-Roman empire were large conglomerations of residential quarters surrounding temples, government offices, market places, and other official buildings; much like cities in our own days.

But the ideal of the polis as ‘community’ was never completely lost. The polis existed to serve its citizens. The citizens of Antioch, Alexandria, Ephesus and Philippi would keep reminding their magistrates of it. Christian Scriptures also allude to this ideal in visions of the heavenly city. ‘We have no permanent city here on earth; we are looking forward to the city which is to come’. (5) The future community of God with his beloved people is portrayed as a ‘new City (polis), the New Jerusalem’.

‘God has made his home with human beings!

He will live with them, and they shall be his people.

God himself will be with them, and they shall be his people. He will wipe away all tears from their eyes. There will be no more death, no more suffering or mourning or pain ....

I did not see a temple in the city, because God himself is its temple, the Lord Almighty and the Lamb. The city has no need of sun or moon to shine on it, for the radiance of God illuminates it and the Lamb is its lamp.’ Revelation 21,1-27; esp. vs. 3-4, 23-24; see also 3,12.

This picture of happiness and communal harmony was a far cry from the stark reality of rivalry and poverty most urban Hellenists had to face every day. But even in the midst of congestion and squalor, they would be proud of their city’s institutions and dream of prosperity for all.

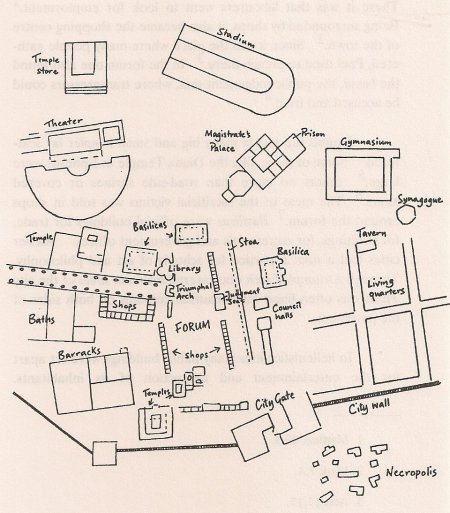

Typical public buildings in a hellenistic city. The exact lay-out would vary from town to town. |

Practically all hellenistic cities possessed the same pattern of public buildings. Although they could be differently shaped and grouped, the same public institutions reappear in every city so far excavated. It is much like in our own days. Does every town or city of any size not have its railway station, town hall, banks, supermarkets, stadium, and so on? We find a similar, universal ‘city culture’ in hellenistic times.

The heart of the hellenistic city was an open square: the agora (Greek name) or forum (Latin name). There it was that all official business, such as electing magistrates, was conducted. There it was that labourers went to look for employment. (6) Being surrounded by shops, it also became the shopping centre of the town. (7) Since it was the place where many people gathered, Paul used to preach there. (8) In the forum one also found the bema, the public judgement seat, where transgressors could be accused and tried. (9)

Round the forum many big and small temples lay scattered. Some of these, like the Diana Temple in Ephesus were large,(10) others no more than road-side shrines or covered altars.(11) The meat of the sacrificial victims was sold in shops around the forum. (12) Basilicas were official buildings for trade, for meetings, for secret trials and government offices. Richer cities had a stoa: a portico for schools of art and philosophy. Through a triumphal arch one entered the main street of the city which was often lined with beautiful columns on both sides of the pavement.

In hellenistic cities many public buildings were set apart for the entertainment and instruction of its inhabitants. Gymnasiums were for sport. They provided grounds and equipment for intensive exercises in wrestling, discus throwing and jumping. Tyrannos’ schola in Ephesus may have been the hall of a private sports trainer. (13)

Public baths, called thermae, had cloak-rooms, basins for washing (hot, tepid and cold water), and massage rooms complete with couches and anointing equipment. A library lent out book scrolls. From time to time plays were performed in the theatre and races in the stadium. (14) The theatre was also used for mass meetings. (15)

People’s residential quarters were usually well planned as square blocks of houses within a grid of straight roads. Sometimes the houses were small flats in two or three-storey structures. There were taverns and wine-shops, (16) public latrines, laundries, bakeries, potteries, oil-presses. In later times the big cities had their fire-fighting service and a sewage system to rid the towns of drainage. Also aquaducts bringing in fresh water from many miles away were not rare.

The Jews would use some hall as their synagogue. (17)

|

Actors and actresses wore masks to express

characters. |

Theatre, a Greek invention, means ‘place of

seeing’. The actors performed on the stage behind the orchestra

circle. |

Cities were protected by huge walls that surrounded them completely. (18) The city gates were closed at night and were guarded by the city’s police and armed forces. (19) These maintainers of law and order were stationed in barracks. (20) Special gaolers were in charge of prisoners. The prisons themselves were small rooms or pits near the magistrate’s house or near the barracks. (21)

Outside the city white monuments or tombs (22) indicated the place of the graveyard, called necropolis (‘town of the dead’). Rich families would possess their own plot of ground in this cemetery. (23)

The real force shaping the old cities, like our cities today, was far-reaching economic change. In traditional farming societies, survival has always depended on people producing their own food, with some exchange of natural goods. The ideal village was self supporting. It produced more or less what the community needed.

Mass production began to alter this pattern. Farmers in one place could harvest large quantities of wheat and barley, whereas somewhere else the land might yield plenty of olive oil and wine. When farmers laid up their crops in large store rooms, they found these needed protection from robbers. Walls were built and soldiers appointed to guard the gates. Leaders were elected to organise defence and distribution. The city, with a king and an army, had been born.

|

Money was invented to facilitate trading goods with neighbouring cities. Containers needed to be manufactured, like pots to hold wine and bottles to hold perfume. Deals began to be registered on clay tablets.

This in turn called for scribes who could write and accountants who could keep records.

Economists describe this development by saying that primary production (agriculture) gave rise to secondary production (manufacturing) and tertiary production (trade and services). (24)

It was such mass production in the 5th millennium BC that created the first empires along the great rivers of the Tigris and Euphrates in Mesopotamia and along the Nile in Egypt. A similar economic development can be documented for the Yang-Shao culture in third-millennium China, for the Harappa civilization of ancient India, for the Incas and Mayas in Central America. The hellenistic cities of the Graeco-Roman Empire were in a first stage of this ‘modern economy’.

It is beyond the scope of this book to analyse modern market economy in detail, but it may be useful to recognise four economic factors, which were at work in a city like Corinth, and which are still crucial today.

Advancing technology demands an ever greater differentiation of tasks. In Paul’s Corinth there were skilled workers of many kinds. Building required an architect, stone cutters, masons, carpenters, engineeers, artists to paint frescoes and lay mosaics, and clerks of works. Manufacturing required dozens of specialists: from glass blowers to coppersmiths and wheel- wrights. Expert knowledge produced quality results.

|

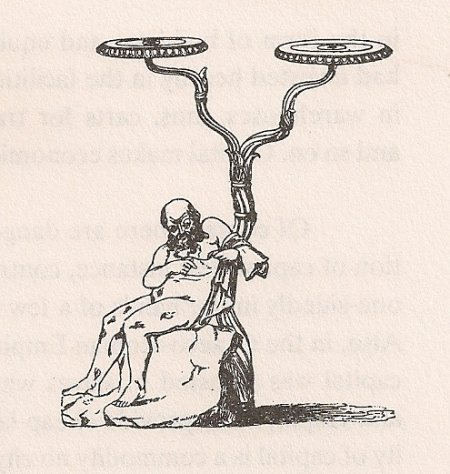

A city’s wealth depends on its trade. Its imports need to be balanced by its exports. Corinth’s income was assured by its sale of bronzes (see the lamp stand) and currants. It also ran a profitable tourist business during the Isthmian games, and provided lucrative services to passengers and cargo ships moving through its ports.

A modern economy cannot make progress without the leadership given by enterprising business people. (25) It requires persons with imagination who accumulate capital and are will- ing to take risks. Corinth possessed an upper-class of such wealthy and successful businessmen. Although this may lead to unjustified divisions in society, the need of economic enterprise by gifted individuals is indisputable.

Last not least, there is a need of accumulated capital. (26) With capital, more is meant than just money. Capital may exist in the form of buildings and equipment. Corinth, for example, had invested heavily in the facilities it provided: in the diolkos (paved road, see diagram in Chapter 1) in warehouses, inns, carts for transport, stocks of provisions, and so on. Capital makes economic enterprise possible.

Of course, there are dangers inherent in the accumulation of capital. For instance, control over it may come to reside one-sidedly in the hands of a few individuals and their families. Also, in the Graeco-Roman Empire, a large slice of the existing capital was invested in slaves whom the upper classes owned and employed to provide cheap labour. However, the availability of capital is a commodity no city economy can do without.

I have elaborated these points to illustrate that the economic developments that shaped the hellenistic cities, are still at work today. Accepting Hellenism required a willingness to commit oneself to a modern way of life.

The Jews were also part of the Graeco-Roman world. When Jesus was born, Palestine had been under the rule of Greeks and Hellenists for three centuries. What was the attitude of the Jews towards hellenistic culture?

The overall response was one of keeping themselves separate, apart from the small number of Jews who gave up their own religion and joined hellenistic culture wholesale. In Palestine, many Jews adopted a stand of firm opposition. In the Diaspora, a more diplomatic formula was worked out which may be described as: ‘cooperation in business, but seclusion in life’. Let us look at each of these positions in turn.

The Jews in Palestine lived under the Seleucid kings of Antioch. One of these kings, Antiochus Ephiphanes IV (175- 164 BC), initiated a programme of hellenization. Recognising that opposition to Greek culture among the Jews flowed from their religious beliefs, he attempted to root out their religion. Keeping the Sabbath and circumcision were forbidden.

The Temple was desecrated by pagan statues. People were forced to offer sacrifices to Greek divinities. A number of Jews accepted all this. Perhaps, they were impressed by Greek culture. Perhaps they simply yielded to political pressure. In the eyes of the Jews they became apostates. The most notorious among them was Jason who officiated as high priest in Jerusalem from 174 to 171 BC. (27)

However, the bulk of the Jews resisted all efforts at hellenization. They initiated a widespread revolt which was guided and directed by Mattathias and his sons. About the heroism of the martyrs and freedom fighters of this epoch we read extensively in the two books of the Maccabees.

The spiritual heritage of the struggle was continued in groups such as the Chasidim (the "Pure Ones") and the Pharisim (the "Separated Ones") who wanted to remain as loyal as possi- ble to their own religious traditions. For ordinary people cultural distrust added to the scars of religious persecution.

The country folk in Palestine who spoke Aramaic rather than Greek, regarded the new hellenistic life style followed in the cities with scepticism and resentment.

Quite a different approach was adopted by many Diaspora Jews such as the Jewish community at Alexandria. This city was, outside Greece, the greatest metropolis of hellenistic culture. Here Euclid had elucidated his mathematical principles. Here Kallimachos and Theokritos had begun a new literary tradition. The library at Alexandria which had been augmented with the collection of books owned by the kings of Pergamon, contained perhaps as many as half a million manuscripts, most of which were accessible through its systematic catalogue. The Jews could not but be influenced by this intellectual momentum.

After all, they were part of city life. They lived in two of the five city quarters. They shared the rights of full citizens. They too elected the ethnarch and the elders that formed the municipal government. They took part in the manufacturing and trade of city economy. Rather than reject Hellenism outright, they chose to integrate it as far as possible. Leadership in this was given by such farsighted persons as Aristobolos, a Jewish ethnarch and counsellor (160 BC), Artapanos, a Jewish historian who wrote in Greek (100 BC) and Philo of Alexandria (15 BC - 45 AD), the Jewish thinker who drew on hellenistic philosophy.

It was in Alexandria that the Jews translated the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek. This translation, the so-called Septuagint, was used by Jewish communities throughout the Roman Empire. It was also the universal text adopted by the early Christian communities. Some of the books were written in Alexandria. The Book of Sirach, in its Greek edition, tried to salvage Jewish faith and morality within the transactions of hellenised life. Kohelet and the Book of Wisdom expressed profound Jewish insights in the language of Greek philosophy.

Quite a number of hellenistic cities had been built in Palestine. In Galilee these were: Tiberias, a walled city with warm-water baths, a forum, temples and a stadium; then Sephphoris hardly five miles distance from Nazareth and Magdala, a holiday resort with a race track for horses, the town where Mary of Magdala lived. Other hellenistic cities were Scythopolis, Antipatris, Archelais, Gerasa, Gadara and Caesarea. All these places had fine hellenistic buildings which still impress tourists today who visit the ruins that have been pre- served of them. Much of the day’s business in such cities was, we can be sure, conducted in Greek.

There were Hellenists in the more traditional towns too. Zaccheus, though a Jew, is an example of one. He lived in the trading city Jericho. He was attracted to Hellenism because he saw its obvious advantages. It made you somehow a man of the world. It opened a treasury of new knowledge, of Greek philosophy and Greek know-how. It brought with it a new living standard, more wealth and prosperity for the elite, a development of the person in body and spirit. It was so exciting to watch a Greek tragedy in the theatre, to visit the baths or to entertain international travellers at home.

But Hellenism also posed spiritual risks. It was easy to give in to the wishes of shrewd politicians or to adopt the unscrupulous ways of rich merchants. Some Hellenists, like Herod Antipas, were degenerate pleasure seekers. Others exploited the poor and became indifferent to God and his moral demands. By siding wholeheartedly with a powerful, international elite, Zaccheus was on a slippery path.

It is interesting to observe Jesus’ attitude to Hellenism. Like the majority of devout Jews, Jesus recognised the dangers of the hellenistic lifestyle. As far as we know, he never entered the hellenistic cities, even those that were near at hand, such as Tiberias, Sephphoris and Magdala. Jesus reserved his ministry to the simple country folk whose language he spoke. And he gave his instruction to his apostles when he sent them out for the first time: "Do not go to the Gentiles (that is: the Hellenists) and do not enter a Samaritan town. Rather go to the lost sheep of the house of Israel".(28)

On the other hand, we do not find that Jesus attacked Hellenists or treated them as enemies. On the contrary, when they approached him he met them with kindness and consideration.

John mentions that some Greeks wanted to see Jesus and did so through Philip who, as we can see from his adopted name, certainly spoke Greek. (29) Jesus was kind to Mary of Magdala, a Jewish girl who probably served in a hellenistic tavern. (30)

Jesus’ visit to Zaccheus’ home is significant in this context. He accepts Zacheus’ hospitality to show that his Kingdom is also for Hellenists. ‘Salvation has come to this house.’ Zaccheus does not need to renounce his hellenistic way of life; only his unjust practices. ‘This man too’, Jesus says, ‘is a son of Abraham’, even though he is a Hellenist.(31)

Luke, the author of the Gospel, was a Hellenist himself, probably from Antioch in Syria. Luke wrote his Gospel for the many Christian communities that had been established outside Palestine, among Hellenists. This helps us to understand why Luke chose this passage on Zaccheus and similar passages for his Gospel. He wanted to reassure his readers that there was nothing wrong in being a Hellenist in itself; but that city people, like everyone else, need to convert and live up to the principles of the Kingdom.

QUESTIONS FOR STUDY

1. The following Greek terms were important in New Testament times. Can you describe what they meant?

koine theatre diaspora Septuagint basilica polis gymnasium Hellenist

2. Why would Hellenists easily identify with the following persons mentioned in Luke’s Gospel?

Theophilos, to whom Luke addressed his Gospel (Luke 1,1);

the sinful woman (Luke 7,36-50);

Herod Antipas (Luke 9,7-9; 23,6-12);

Joanna, whose husband Chusa served in Herod’s court (Luke 8,3);

the unbelieving judge (Luke 18,1-8);

Simon of Cyrene who carried Jesus’ cross (Luke 23,26);

the army officer under the cross (Luke 23,47).

3. Life in our big cities today seems to destroy the sociological base on which people’s religion was grounded. By and large there is a decline in organised religious practice. Church structures, such as the parish, arose in rural conditions and do not easily fit into an urbanised setting. Moreover, urban people find it difficult to harmonise the black-and-white morals of the past with the far more complex moral issues implied in modern business, politics, news media, health and social care.

The Early Church struggled with the task of translating the Gospel for the city people of their time. How can we do the same for the secularised, urban people of today?

1. Poleis is the plural of polis.

2. In the New Testament ekklêsia is also the term to describe the ‘Church’ (the assembly of the faithful). A fuller explanation of this word can be found in Together in My Name, pp. 61 - 64.

3. Politics was the public business of governing the state; our word derives from this, with its associated term: politicians. A policy was a common decision.

4. About the concept of the polis there are classical descriptions in ARISTOTLE’S Politics, especially Book IV, and PLATO’s Republic. See also: R.E.TURNER, The Great Cultural Traditions, vol. I, ‘The Ancient Cities’, London 1941; CH.HIGNETT, A History of the Athenian Constitution, Oxford 1952; W.G.FORREST, The Emergence of Greek Democracy, 800 - 400 BC, London 1966; H.D.F.KITTO, The Greeks, Harmondsworth 1979.

| 5. Hebrews 13,14. | 6. Matthew 20,3. | 7. Mark 7,4. | 8. Acts 17,17. |

| 9. Acts 16,19; 12,21; 18,12-17. | 10. Acts 19,27. | 11. Acts 17,23. | 12. 1 Corinthians 8,4-13. |

| 13. Acts 19,9. | 14. 1 Corinthians 9,24. | 15. Acts 19,29; see also 1 Corinthians 4,9. | 16. Acts 28,15. |

17. A synagogue was a congregation of Jews gathering on the Sabbath day to listen to readings from the Scriptures and to recite prayers. Also the hall where they met was called synagogue.

18. Acts 9,25; 2 Corinthians 11,33.

19. Acts 9,24; 12,19; 16,13.

20. Matthew 27,27; Acts 23,35; Philippians 1,13.

21. Acts 5,19; 8,3; 12,4-10; 16,23-30.

22. Matthew 23,27; 27,59-66.

23. The term cemetery (lit. ‘sleeping place') is of Christian origin. Christians believed that deceased persons had ‘fallen asleep’ and would rise on the last day (1 Thessalonians 4,13-18). It was the Christians who buried the dead in their places of worship (catacombs and churches) and who brought graveyards within city walls.

24. Read such classic works as: C.CLARK, The Conditions of Economic Progress, New York 1951; W.W.ROSTOW, The Stages of Economic Growth, New York 1960.

25. This factor is brought out well by J.A.SCHUMPETER, Business Cycles, Chicago 1933.

26. For classic descriptions of capital and its functions, see: J.M.KEYNES, General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, San Diego 1936; J.K.GALBRAITH, The Affluent Society, London 1958; S.KUZNETS, Capital in the American Economy, Salem 1962.

| 27. 2 Maccabees 4,7-20. | 28. Matthew 10,5-6. | 29. John 12,20-22. | 30. Luke 7,36-50. | 31. Luke 19,1-10. |